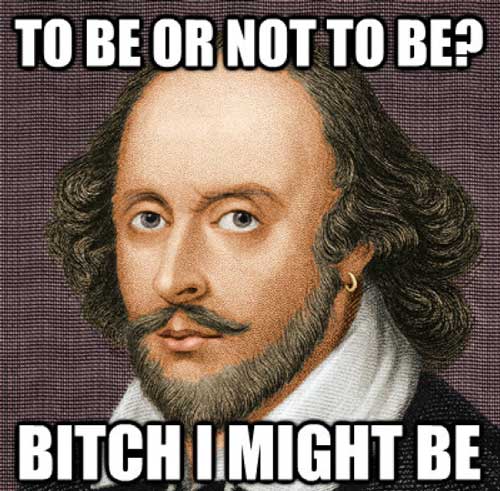

I love writing that plays with language, and in this respect, Shakespeare is my personal bitch.

Sonnet 116—made popular in the movie adaptation of Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility—is a great example of his art in action. I’ll list out my thoughts and then the full sonnet because, hey, it’s my blog and this is what I’ve been obsessing about lately!

SONNET 116

Lets start with the title. This guy wrote 115 of these before he got to 116. That’s a shit-ton of poetry. Shakespeare wasn’t alone in his obsession with words, either. In this time period, writing was king, mostly because there was no TV, movies, video games, publishing and the Internet. As a result, you played around with words. Like, a lot. As a writer, I totally fantasize about that word-centric existence. Well, about visiting it anyway.

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Great phrase here: marriage of true minds. Back in Bill’s day, true meant more ‘faithful’ than it does now. And the use of the word marriage is a whopper. This is a religious-laden time period. Think we have issues with marriage? Bloody Mary just got done barbecuing people for having different thoughts on the subject. And here, our boy Bill writes about marriage separate from religion and it’s not even specified to a woman. Go Bill! That’s balls. It also suggests some secularism, which sets him up for the next section.

Admit impediments. Love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove:

Two things I adore about this passage. First, it’s not the ‘your eyes are like limpid pools’ lovey-dovey bullshit that was often written around this time. Nope, Shakespeare goes right for the echoing of Corinthians. This is one of my favorite bible passages and by echoing it, Bill is showing some more balls. Which side is he on? Catholic Bloody Mary or Anglican Elizabeth? Many scholars suspect the Catholic side. As a writer, what impresses me is that Shakespeare is not only writing a great poem about love, he’s also expertly navigating the politics of the time to keep his head firmly attached to his shoulders by gently courting both sides of the issue. That’s effing brilliant.

Here’s the second power-writer part of this section. It’s a rule that writers aren’t supposed to use the same description words twice within the same sentence, or even side-by-side sentences. Example: “She walks in beauty like a beautiful person” is shitty writing compared to “She walks in beauty like the night.”

Shakespeare kicks that rule on its ass by finding not one, not two, but three double uses of a word within the same fucking sentence and totally makes it work. There’s love > love, alters > alteration, and remover > remove. It’s just so gorgeous, I want to cry. It also makes a subtle point about the common conception of love and its reality. Brilliant.

O no; it is an ever-fixed mark,

That looks on tempests, and is never shaken;

I love the phase “looks on tempests and is never shaken.” Why? Because once you hit the damned tempest, you are totally shaken. You might even get killed. Again, Shakespeare avoids the trite “love conquers all” as an easy way out and really explores his subject matter here. And we’re at line six, people.

It is the star to every wandering bark,

Whose worth’s unknown, although his height be taken.

A bark is a ship, so this is another nice image of love as the North Star. Awwwww. ‘Height be taken’ is about measuring the stars as part of navigation. Another great image and symbol of love.

Love’s not Time’s fool, though rosy lips and cheeks

Within his bending sickle’s compass come;

I like this part too. Rosy lips and cheeks got a lot of air time in poetry of the era, so Shakespeare is taking aim at the practice of loving beauty over love itself. It’s somehow comforting to know that worshipping appearances was going on back then, too.

Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks,

But bears it out even to the edge of doom.

Can I critique Shakespeare? Yeah, it’s my blog so I can. I feel like he made this point already. If you’re sailing into a tempest, you know all about the edge of doom. This really isn’t adding anything, but just because he’s Shakespeare doesn’t mean I have to adore every word. The first half of the sonnet is my favorite. Jane Austen called it as a classic.

If this be error and upon me proved,

I never writ, nor no man ever loved.

This is a great ending. It’s Dylan Thomas-eque in referring to Shakespeare’s personal experience of love. Which, if this sonnet is any indication, he sees himself as more of a writer than a lover. Not a shocker, considering he left his wife alone at Stratford on Avon for years at a time. What is a shocker is that he may have had the self-awareness to realize that fact.

And here’s the sonnet in full…

SONNET 116

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments. Love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove:

O no; it is an ever-fixed mark,

That looks on tempests, and is never shaken;

It is the star to every wandering bark,

Whose worth’s unknown, although his height be taken.

Love’s not Time’s fool, though rosy lips and cheeks

Within his bending sickle’s compass come;

Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks,

But bears it out even to the edge of doom.

If this be error and upon me proved,

I never writ, nor no man ever loved.

On a final note, I love how Shakespeare did all this phenomenal writing without having been part of the cultural elite of his time. Guess what? It still irks the cultural elite to this day. There’s no end to the movies, papers and pontifications about how Bill was really some kind of Brit noble going incognito so he can work crazy-hard for a living.

Because, you know, rich nobles do that kind of thing all the time.

IMHO, our friend Bill was just a quill-wielding guy living in the middle of nowhere who had a massive gift-slash-obsession with language. Go you, Bill. Give them hell.